What is a Steer? Complete Guide to Steers and Cattle Production

When discussing cattle production, understanding the terminology is essential for both industry professionals and curious consumers. A steer is a male bovine (cattle) that has been castrated before reaching sexual maturity, typically before it’s one year old.

This process, which removes the testicles, prevents the animal from developing the masculine characteristics associated with bulls, resulting in meat that is generally more tender, consistent in quality, and preferred by consumers.

Steers play a crucial role in beef production worldwide, representing a significant portion of the cattle raised specifically for meat. Unlike bulls (intact males) or cows (adult females that have given birth), steers are specifically managed for optimal meat production.

Their unique physiological development after castration leads to different growth patterns, fat distribution, and ultimately, meat characteristics that the beef industry values highly.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore everything you need to know about steers—from their biological definition and physical characteristics to their role in global beef production, management practices, and cultural significance.

Whether you’re a farmer looking to optimize your cattle operation, a student studying animal science, or simply someone interested in understanding where your food comes from, this article will provide valuable insights into the world of steers and cattle production.

The Biological Definition: What Makes a Steer Different from Other Cattle

Physiological Characteristics of Steers

A steer is biologically distinct from other cattle classifications due to its castrated status. When a young male calf is castrated, the removal of testicles eliminates the primary source of testosterone production. This hormonal change creates several physiological differences that distinguish steers from bulls:

Reduced Muscle Development: Without testosterone, steers develop less pronounced muscle mass, particularly in the neck and shoulder regions, compared to bulls.

Fat Distribution: Steers tend to deposit fat more evenly throughout their bodies, including intramuscular fat (marbling), which is highly desirable in beef production.

Bone Structure: Steers typically have less dense bone structure than bulls, contributing to higher dressing percentages (the proportion of carcass weight to live weight).

Temperament: The absence of testosterone results in a generally calmer, less aggressive temperament, making steers easier to handle and manage in groups.

Steer vs. Bull vs. Cow: Understanding Cattle Classifications

| Term | Sex | Castrated? | Age | Primary Purpose | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bull | Male | No | Adult | Reproduction | Muscular, thick neck, aggressive temperament |

| Steer | Male | Yes | Adult | Meat production | Less aggressive, raised for beef |

| Cow | Female | No | Adult (has calved) | Reproduction, milk production | Mature female that has given birth |

| Heifer | Female | No | Young (not calved) | Future reproduction | Young female, has not given birth |

| Ox | Male | Yes | Adult | Draft/work animal | Trained for pulling loads |

| Calf | Male or Female | N/A | Under 1 year old | Growth, breeding, or meat | Young, dependent on milk |

The History and Development of Steer Production in Agriculture

Historical Context of Cattle Castration Practices

Castrating male cattle is a very old practice, used for thousands of years in places like ancient Egypt, Rome, and China. Farmers learned that castrated males were calmer and easier to handle than bulls. They were also better work animals (called oxen) because they were more steady and strong.

Even back then, people noticed that meat from castrated cattle was softer and tasted better. Over time, the ways of castration have improved a lot. Today, modern methods focus on being more humane and safe for the animals, while still helping farmers raise healthy and useful cattle.

Evolution of Modern Steer Production Systems

Modern steer production has evolved into a sophisticated system that combines traditional knowledge with scientific advancements:

Specialized Breeding: Selection of specific cattle breeds based on their growth characteristics, feed efficiency, and meat quality. Nutritional Science: Development of optimized feeding programs that maximize growth while maintaining health and meat quality. Health Management: Implementation of comprehensive vaccination and parasite control programs to ensure steer health and productivity.

Genetic Improvements: Utilization of genetic selection and, more recently, genomic testing to identify superior animals for breeding programs that ultimately produce better steers.

This evolution has resulted in significant improvements in production efficiency, meat quality, and animal welfare standards across the global beef industry.

Common Breeds Used for Steer Production

Popular Beef Cattle Breeds for Steers

Different cattle breeds offer various advantages in steer production, with producers selecting breeds based on their specific goals, climate conditions, and market demands. Here are some of the most common breeds used for steer production:

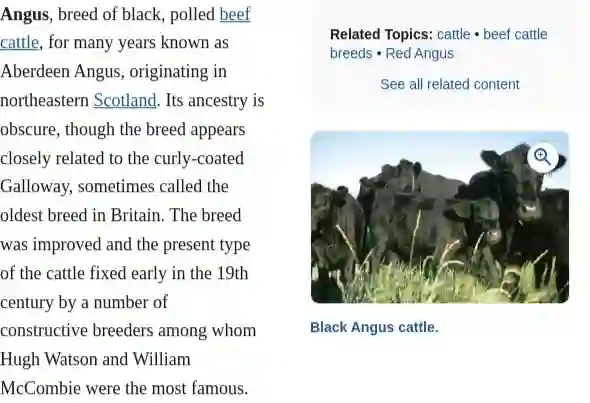

Black Angus

Black Angus cattle have become the dominant breed in North American beef production, particularly for steer operations. Their popularity stems from several key characteristics: •Superior Marbling: Angus steers typically develop excellent intramuscular fat, leading to well-marbled beef that grades higher on quality scales.

Moderate Frame Size: Their medium frame size allows for efficient finishing at market-preferred weights. •Calving Ease: Angus cows generally have fewer calving difficulties, resulting in healthier calves that make better steers.

Feed Efficiency: They convert feed to muscle efficiently, an important economic consideration in steer production.

Polled Genetics: Most Angus cattle are naturally hornless (polled), eliminating the need for dehorning.

Hereford

Hereford cattle, recognizable by their distinctive red body color and white face, are another popular choice for steer production:

Hardiness: Herefords demonstrate excellent adaptability to various climates and conditions.

Foraging Ability: They perform well on pasture-based systems with less supplemental feed.

Docile Temperament: Their generally calm disposition makes them easier to handle.

Crossbreeding Value: Herefords cross well with other breeds, particularly Angus (creating “black baldies”), combining the best traits of both breeds.

Charolais

Originally from France, Charolais cattle have become important in steer production systems worldwide:

Growth Rate: Charolais steers are known for their exceptional growth rate and large frame size.

Muscling: They develop outstanding muscle mass, resulting in high yields of lean meat.

Crossbreeding Performance: When crossed with British breeds like Angus or Hereford, the resulting steers often exhibit hybrid vigor with improved growth while maintaining meat quality.

Feed Conversion: Despite their large size, they demonstrate good feed conversion efficiency.

Brahman and Brahman-Influence Breeds

In warmer climates, particularly in southern regions of the United States, subtropical, and tropical areas worldwide, Brahman and Brahman-influenced breeds are preferred for steer production:

Heat Tolerance: Their distinctive hump, loose skin, and efficient sweat glands provide superior heat tolerance.

Parasite Resistance: Brahman cattle demonstrate better resistance to ticks and other external parasites.

Hybrid Vigor: When crossed with European breeds, the resulting steers often show exceptional hybrid vigor.

Adaptability: They thrive in challenging environments where other breeds might struggle.

Crossbreeding Strategies for Optimal Steer Performance

Modern steer production often utilizes strategic crossbreeding to combine the best traits of different breeds:

Terminal Cross Systems: Using maternal-focused breeds for the cow herd and growth-focused breeds for the sire, producing steers that benefit from complementary traits.

Composite Breeding: Developing stabilized crossbreeds that incorporate desirable traits from multiple breeds.

Rotational Crossbreeding: Systematically rotating breeds of sires to maintain hybrid vigor while keeping a consistent type of animal.

Breed Complementarity: Selecting breeds that specifically complement each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

The ideal crossbreeding strategy depends on the producer’s specific goals, resources, and market targets. However, research consistently shows that crossbred steers often outperform purebreds in growth rate, feed efficiency, and overall production economics.

The Lifecycle of a Steer: From Calf to Market

Early Development and Weaning Process

The journey of a steer begins at birth as a bull calf. During the first few months of life, the calf remains with its mother, nursing and gradually beginning to consume forage. This period is critical for establishing a healthy immune system and setting the foundation for future growth.

Key milestones in early development include:

Birth to 3 Months: Primary nutrition comes from the mother’s milk, with gradual introduction to forage and sometimes creep feed (supplemental feed provided to calves while still nursing).

Castration: Typically performed between 1-3 months of age, using methods such as surgical removal, banding, or burdizzo (a bloodless method using a clamp). Modern practices increasingly incorporate pain management.

Weaning: Usually occurs between 6-8 months of age, when the calf is separated from its mother. This is a significant stress point in the animal’s life, and various weaning strategies are employed to minimize stress:

Fence-line weaning: Calves and cows are separated by a fence but can still see and hear each other

Two-stage weaning: Using nose flaps that prevent nursing before actual separation

Yard weaning: Calves are placed in yards with good feed and water for a period before pasture placement

Post-weaning Management: After weaning, the newly designated steers typically enter a growing program focused on frame development rather than fattening.

Growth Phases and Feeding Regimens

The growth of a steer follows distinct phases, each with specific nutritional requirements and management practices:

Growing Phase (Weaning to ~700-800 pounds)

During this phase, the focus is on skeletal and muscle development rather than fat deposition:

Nutrition: Moderate-energy diets, often forage-based with protein supplementation

Growth Rate: Targeted at 1.5-2.5 pounds per day, depending on frame size and breed

Management: Emphasis on health protocols, including vaccinations and parasite control

Finishing Phase (800+ pounds to Market Weight)

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Phase Name | Finishing Phase |

| Goal | Add weight and fat to meet market standards |

| Nutrition | High-energy diet with more grains |

| Growth Rate | 3+ pounds per day (in conventional systems) |

| Management | Careful monitoring of feed intake and overall health |

| Result | Well-finished cattle ready for processing with proper meat and fat balance |

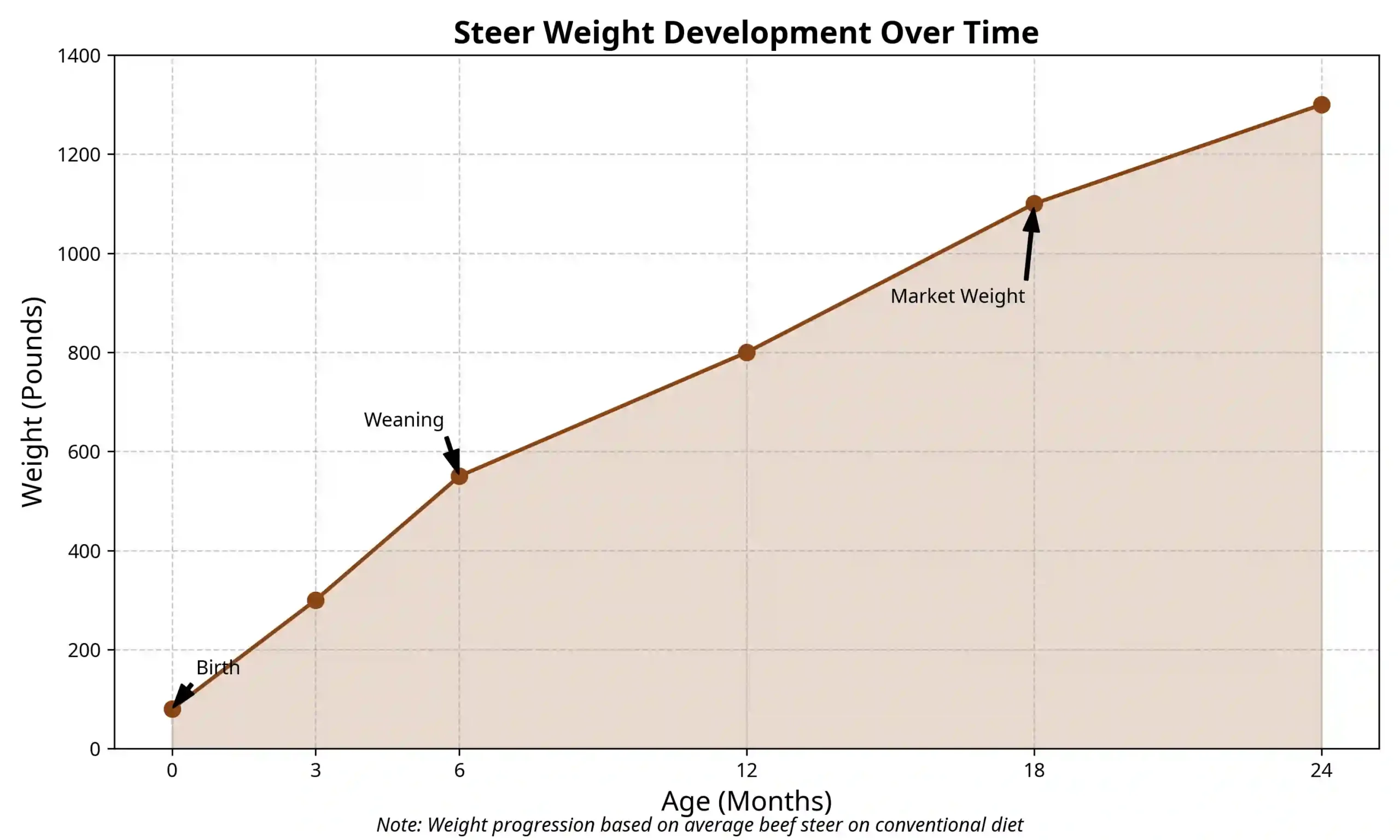

The graph below illustrates the typical weight development pattern of steers from birth to market:

Feedlot Operations vs. Grass-Finished Production

Two primary systems dominate steer finishing in modern beef production:

| Aspect | Conventional Feedlot | Grass-Finished |

|---|---|---|

| Housing | Pens with feed bunks & water | Pasture-based with rotational grazing |

| Nutrition | High-energy grain-based diets | High-quality forage, minimal concentrates |

| Duration | 120–200 days | 18–24+ months total age |

| Advantages | Fast growth, consistent beef, year-round production | Lower input cost, eco-friendly image, natural appeal |

| Challenges | High costs, manure handling, public perception | Seasonal limits, longer time, needs strong pasture management |

| Market Fit | Efficient, large-scale beef production | Niche markets, health/environment-conscious consumers |

Physical Characteristics and Development of Steers

Anatomical Features and Growth Patterns

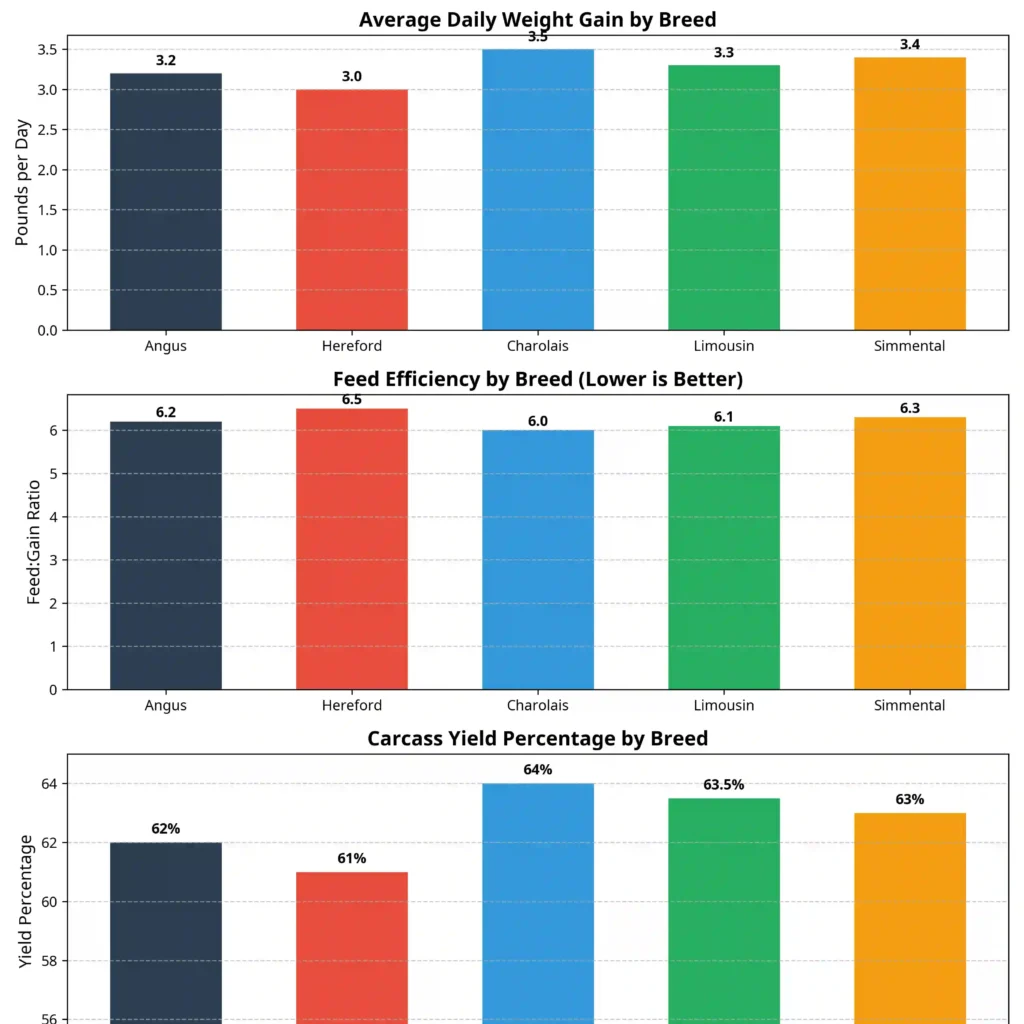

Breed Comparison: Growth Rates and Physical Traits

Different breeds show distinct growth patterns and physical development as steers:

The chart above compares key performance metrics across major beef breeds when raised as steers. Continental European breeds like Charolais and Limousin typically show superior growth rates and muscling, while British breeds like Angus and Hereford often excel in marbling development and reach optimal finish at lighter weights.

Steer Management Practices in Modern Agriculture

| Category | Key Factors |

|---|---|

| Nutrition & Feed Management | • High feed cost (60–70% of total) • Energy: ↑ grain in finishing (60–70%) • Protein: 13–16% (young), 11–13% (finishing) • Minerals: focus on Ca:P balance • Additives: ionophores, probiotics • Consistent feeding, bunk space, proper delivery |

| Health & Disease Prevention | • Vaccinations: IBR, BVD, BRSV, PI3, clostridia • Parasite control: deworming, ectoparasite care • New steers: stress care, electrolytes • Daily checks: watch feeding, breathing, lameness • Clear treatment protocols, responsible antibiotic use |

| Environmental Sustainability | • Manure: managed for fertilizer, low odor/runoff • Water: buffer zones, controlled access • Land use: smart grazing & stocking • GHG: cut emissions via feed & manure strategy • Conserve water, feed, energy |

Economic Importance of Steers in the Beef Industry

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Weight Categories | • Lightweight: 400–600 lbs • Heavy feeders: 600–800 lbs • Yearlings: 800–950 lbs • Fat cattle: 1,100–1,400+ lbs |

| Quality Grades | • Prime: Excellent marbling (3–5% of beef) • Choice: Moderate marbling (most common) • Select: Slight marbling • Standard: Minimal marbling |

| Yield Grades | Ranges from Grade 1 (leanest, most meat) to Grade 5 (least lean) |

| Seasonal Patterns | Prices peak in spring/early summer due to limited supply |

Value-Added Programs & Premium Markets

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Weight Categories | • Lightweight: 400–600 lbs • Heavy feeders: 600–800 lbs • Yearlings: 800–950 lbs • Fat cattle: 1,100–1,400+ lbs |

| Quality Grades | • Prime: Excellent marbling (3–5% of beef) • Choice: Moderate marbling (most common) • Select: Slight marbling • Standard: Minimal marbling |

| Yield Grades | Ranges from Grade 1 (leanest, most meat) to Grade 5 (least lean) |

| Seasonal Patterns | Prices peak in spring/early summer due to limited supply |

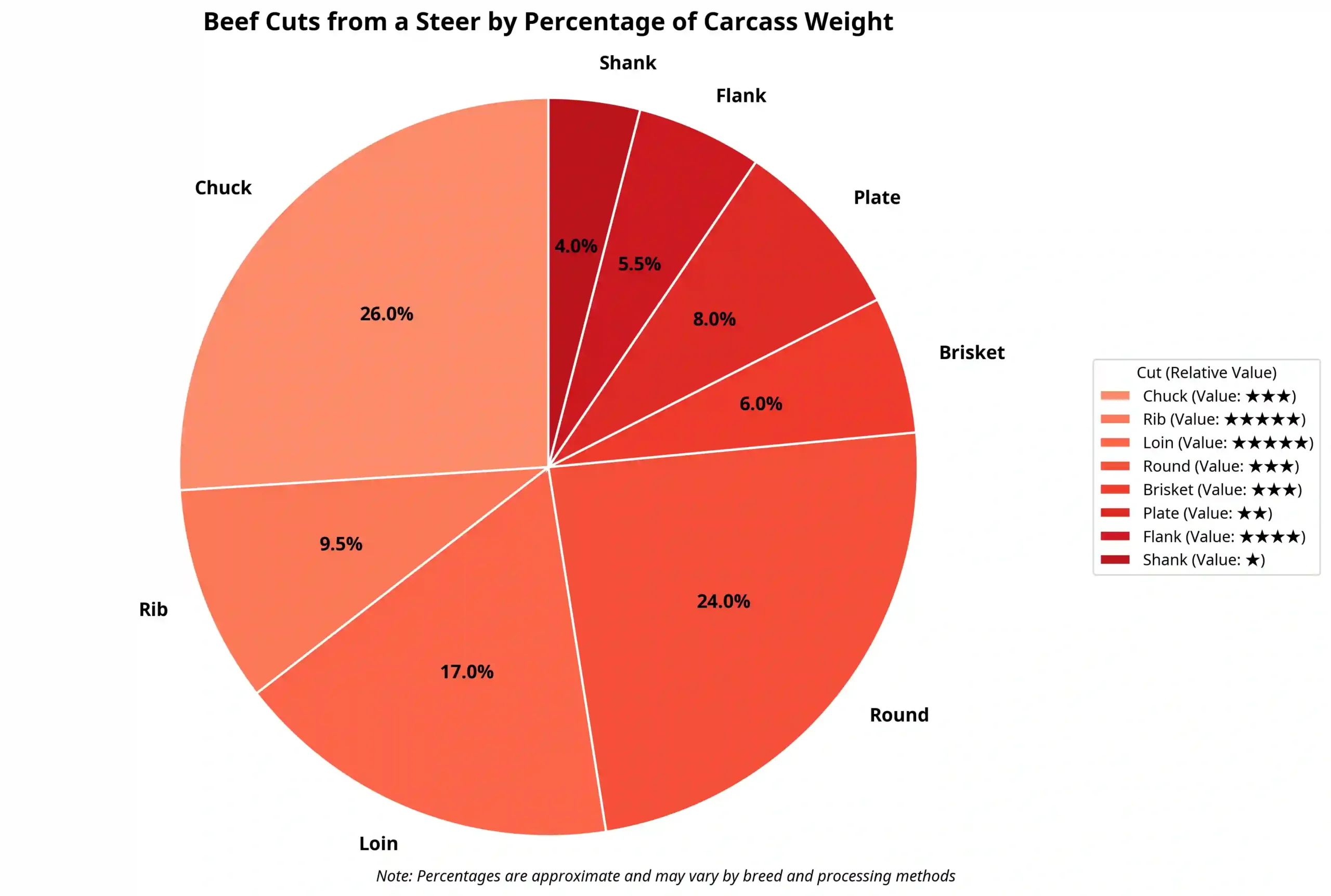

Understanding Beef Cuts and Their Origins

The carcass of a steer is divided into primal cuts, which are further processed into the retail cuts consumers recognize. The main primal cuts include:

Chuck: From the shoulder area, representing about 26% of carcass weight. Yields economical cuts like chuck roast and ground beef.

Rib: Contains the highly valued ribeye steak, prime rib, and back ribs, making up approximately 9.5% of carcass weight.

Loin: The most valuable section per pound, containing premium steaks like tenderloin (filet mignon), T-bone, porterhouse, and strip steak. Represents about 17% of carcass weight.

Round: From the rear leg, making up approximately 24% of carcass weight. Yields leaner cuts like round steak, rump roast, and eye of round.

Brisket, Plate, and Flank: These sections provide specialized cuts like brisket, skirt steak, and flank steak, collectively representing about 19.5% of carcass weight.

The distribution and relative value of these cuts are illustrated in the following chart:

Factors Affecting Meat Quality in Steers

Several key factors affect the quality of beef from steers. Genetics play a major role, as certain breeds are more likely to produce tender, flavorful, and well-marbled meat.

Age at harvest is also important steers processed between 15 to 24 months generally yield more tender beef.

Nutrition impacts both taste and appearance; grain-fed steers tend to have more marbling and a milder flavor, while grass-fed steers may have yellowish fat, a distinct flavor, and more omega-3s.

Handling before slaughter is critical stress can cause dark, firm, and dry (DFD) meat with reduced shelf life. Lastly, post-harvest aging, typically for 7–21 days, improves tenderness through natural enzymatic activity.

The Cultural Significance of Steers in Different Societies

Steers in Agricultural Traditions and Rural Life

Throughout history, steers and oxen have played pivotal roles in agricultural development and rural culture:

Steer Facts Table: Essential Information at a Glance

| Characteristic | Details |

| Definition | A male bovine castrated before sexual maturity |

| Age at Castration | Typically 1-3 months of age |

| Common Castration Methods | Surgical removal, elastic banding, burdizzo (crushing) |

| Weight at Birth | 60-100 pounds (27-45 kg) depending on breed |

| Weight at Weaning | 450-700 pounds (204-318 kg) at 6-8 months |

| Typical Market Weight | 1,200-1,400 pounds (544-635 kg) |

| Age at Market | 15-24 months typically |

| Feed Conversion Ratio | 6:1 to 8:1 (pounds of feed per pound of gain) |

| Daily Weight Gain (Growing) | 1.5-2.5 pounds (0.7-1.1 kg) per day |

| Daily Weight Gain (Finishing) | 3.0-4.0 pounds (1.4-1.8 kg) per day |

| Water Consumption | 8-20 gallons (30-76 liters) per day depending on size and temperature |

| Dressing Percentage | 60-64% (percentage of live weight that becomes carcass) |

| Typical Carcass Weight | 720-900 pounds (326-408 kg) |

| Primary Breeds Used | Angus, Hereford, Charolais, Simmental, Limousin, Brahman crosses |

| Lifespan (if not harvested) | 15-20 years potential |

Conclusion

Steer production is rapidly evolving with new technologies like GPS tracking and genomic selection improving efficiency and animal care. Sustainability efforts are growing, with a focus on better grazing, lower emissions, and resource conservation.

Consumers now seek transparency, driving innovations like blockchain for traceability. Alternative models such as grass-fed and regenerative systems are gaining popularity. Understanding steers and their role in agriculture helps people make informed, ethical food choices while appreciating the work behind every cut of beef.